In today’s day and age where information is literally at our finger tips via your smart phone, laptop, and all other technology, it is no surprise when clients come into the clinic armed with excellent information.

However, it is far too common that out-dated information, old wives tales, and unfounded statements are being perpetuated. As with all information, we must be a consumer of information. How do you know what you are reading online is accurate, up-to-date, evidence based, current and progressive for treatment and care? Unfortunately, creating a critical mindset towards what is being presented, and for what purpose, and by whom, often is not taught in school until AFTER reaching university. What does this lead to? Potential difficulty consuming information.

Regrettably, it’s not just the world wide web that is spreading misinformation and falsities, but other well-meaning family members, friends, and, healthcare providers. How does this happen? Some providers must know information across a wide variety of areas, whereas some providers practice in very specific areas or specialties. In both instances the provider will have difficulty either a) keeping up with all the new information coming in through the large variety of areas they need to know or b) they are very well informed in their area of specialty, but haven’t kept up in other practice areas.

For our women’s health, prenatal and post-partum clients, we have seen a trend of misinformation come in that we would like to address piece by piece to help those that may be experiencing similar issues/symptoms figure out what is best for them.

Pain during pregnancy is normal and will go away after delivery

Often our prenatal moms come in with significant pain. Ranging from pubic symphysis pain (‘lightning crotch’, groin pain, etc) through SIJ pain (low back and pelvic pain) and sciatica (pain radiating down the leg) to name but a few common pregnancy-related complaints. Although pain during pregnancy is common, it should not be considered normal. We are often explained that during pregnancy the hormone relaxin ’causes’ pain – however, if this were the case, and relaxin is produced during every pregnancy, then wouldn’t every woman who is pregnant be painful? We know that this is not the case, so why do some women become painful and others do not? In my clinical population I have observed many women who are pregnant that are painful, with the start of their pain experience ranging from within the first few weeks of gestation to the last few weeks. The commonalities between these women with pelvic girdle pain in particular, is a combination of muscle length and strength imbalances around the pelvis (muscles that are tight and/or weak), common posture issues (think the typical ‘pregnant’ stance), and activity levels throughout the day (whether that be not enough or too much).

The good news is, pain in pregnancy is NOT necessarily normal! There are many factors that can be addressed, and truly our bodies are very capable of adapting and changing (I mean they grow tiny humans, that’s pretty amazing). When I was taking my prenatal courses while in the Master’s program, we were still being taught that women who are pregnant could not improve, but we could prevent them from getting worse. In a mere 7 years this dialogue is changing; women who are pregnant can and do improve and often resolve pain during pregnancy when appropriately addressed with conservative treatment such as physiotherapy!

How well we are able to do with each client depends on a multitude of factors: what do you need to do on a daily basis, how many weeks gestation are you, what is your pain level when you get started, did you have pain previously or is it new, and of course, how well are you able to do your provided homework?

Pain with intercourse post-partum is normal – just have some wine and relax

As a pelvic floor therapist, I am sad to say I have heard the recommendation for our clients with dyspareunia (pain with intercourse) to ‘just have some wine’ more times than I have kept track of. This sentiment is often expressed when clients get the courage to bring it up to friends, family and their healthcare providers; usually along with a ‘with time it’ll get better’.

Dyspareunia is something that again is common after labor and delivery, but is not normal. To the surprise of many, this pain can occur in those that have had vaginal deliveries with or without tearing, as well as those that have c-sections (scheduled or emergency). Often when we approach medical providers about dyspareunia, they search for a medical cause such as an infection. When there is no medical cause, women will begin to feel the ‘it’s all in your head’ message.

With a physiotherapy perspective, dyspareunia is approached much differently. In my clinical practice I often see women with pelvic pain that have very tight muscles of the pelvis and pelvic floor, restricted movement through scar tissue (either from the perineal tearing or c-section), as well as a variety of postural changes. Very often, it’s these tight muscles that will recreate ‘the pain’ when palpated (on internal and/or external exam). When the clients’ multiple factors are addressed such as muscle tightness, weakness, postural changes, scar mobility and breathing coordination, the dyspareunia is often improved/resolved. Contrary to our all too common advice to just ‘have some wine’, there are many factors that can be addressed with physiotherapy by a trained pelvic floor therapist. Which brings us to our next point…

You are leaking when you cough/sneeze – do your kegels

I am so thrilled to see an increase in awareness and discussion within a variety of groups and campaigns in regards to pelvic floor! The most common discussion is about leaking, usually with cough, sneeze, lifting, jumping, exercise etc (aka stress urinary incontinence). This is where typically women are told to ‘do your kegels’. GREAT! What does that mean? Often when I am seeing clients in-clinic, the understanding of kegels is incomplete – women are aiming to squeeze the pelvic floor for at least 10 seconds, 10 times in a row since that’s what they had read online or in a magazine. I ask – when you try to strengthen another area of your body, do you squeeze it (make it tight in a single position such as tightening your thigh muscle without moving the knee), hold for 10 seconds, pause and then repeat? I also wonder – when receiving this advice has anyone completed an assessment to check what the problem actually is?

I frequently discuss with my clients how differently we approach pelvic floor health versus the rest of the body. If someone comes into my office because their knee hurts, they expect for me to watch them walk, squat, and move in a variety of ways themselves, have me move it for them, take a look at all the muscles, ligaments and surrounding tissues as well as ensure they are doing whatever exercises or stretches I provide them with properly before going. When people come in for a pelvic floor issue, we are often expecting to receive advice, but do not expect to be touched or examined. Clients would not be happy if they came in and I didn’t once look at their painful knee, so why is it acceptable to expect to have no exam of the pelvic floor? A discussion for another day. Why is the exam important?

Pelvic floor analogy: if someone came into the office with an elbow that was stuck in a bent position (because the biceps is too tight), and their complaint is that they are unable to straighten the elbow to catch their cell phone for instance as it falls off the table in front of them (ie leaking), would strengthening the biceps muscle (ie kegels) be helpful? Likely it will not help, and more often than not, a worsening of symptoms may be observed. This is why it is not surprising to me as a therapist when people come into the clinic and their ‘kegels haven’t worked’. Analogy 2: if the pelvic floor to be functional needs to contract AND relax (think the arm bent as contracted and straight as relaxed), does training that muscle to squeeze help it to bend? Not likely. The pelvic floor needs to lift up and in when contracting, and move down and away when relaxing in order to be functional. To top it off, it also needs to have appropriate coordination with the rest of the muscles of the abdomen and pelvis in order to have optimal function. Having a pelvic floor that’s functional without addressing any other postural or coordination issues of the abdomen is like having a perfect pop-can bottom with crumpled sides and top – it’s just not going to be able to do it’s job.

This means, that each client will have a similar, and yet very different treatment approach to leaking. Although many things look the same, with the majority of my clients having a tight pelvic floor (possibly from all the 10 second squeezes we’ve been doing over the years), the underlying cause of tightness is extremely variable.

Having a diastasis means you’ll always look pregnant

First, what is a diastasis recti? This is commonly referred to as the ‘splitting of the abdominal muscles’. Related to women who are pregnant and post-partum, there are now countless ads, programs and ‘healing’ strategies that are being pushed on women to get rid of their ‘mummy tummy’.

I argue that almost 100% of women who are pregnant, that look pregnant at the time of labor and delivery, will develop a diastasis. The diastasis is meant to allow the growing fetus room as the belly expands rapidly, the rectus abdominis (6 pack ab muscles) just doesn’t stretch quickly enough. The size of the diastasis will be dependent on many factors such as the size of the client, the number of fetuses, how many children they have had, etc. There are things we can encourage prenatal to theoretically decrease the impact of the diastasis, including rolling to the side before sitting up, and eliminating exercises that cause what I refer to as ‘tenting’ of the abdomen (if you’ve ever seen the v-shaped tent on your tummy when you go to sit up – that’s your diastasis). The real changes and major impacts happen post-partum.

The size of the diastasis, the amount of space between the muscles, is what the majority of women who come into my clinic are worried about. “How BIG is the GAP?” “Has it CLOSED enough yet?” In my clinical experience the size of the space is not as important as what the muscles are doing. The function of the muscles is key; both independently, and as a working group of muscles. This is where everyone wants a short answer “What should and shouldn’t I be doing?” “What exercise is going to fix my diastasis?” – and this is where I say; I won’t know unless I am able to do an exam. Not all bodies are created equal and some bodies adapt much more quickly than others from a rehabilitation and healing stand point. This means that for one client doing something like a down-dog in yoga could create excellent and appropriate tension, whereas the next person it could be very dysfunctional and problematic.

If we imagine the diastasis like a zipper that’s undone, the zipper being down doesn’t matter so long as you aren’t straining into it with the abdomen from behind (pushing into the open zipper). Think of doing a crunch, when you go to lift your head and shoulders off the ground what does your tummy do? Does the tummy stay relatively flat while you move, or does it push/balloon forward and become more round? From a movement perspective your tummy should not push forward as you do ‘core’ exercises, and this can be an indication of dysfunction and a potential factor for pain and problems. Now, someone may see me at the clinic and have a 3-4 finger ‘gap’ but be able to keep the abdominals coordinated without any pressure forward, whereas another client may have a 1-2 finger gap but be unable to hold appropriate tension.

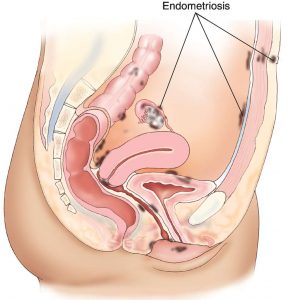

Endometriosis – young girls, women; painful menses is ‘normal’

A diagnosis for endometriosis requires a surgical procedure to examine for the presence of lesions of uterine-like tissue outside of the uterus. What happens is this tissue continues to work the same as the tissue that is within the uterus, and can lead to fibrous tissue and issues within the pelvis. Often women live with common symptoms of endometriosis starting in their teens and it takes years to achieve a diagnosis. In addition, young women and teens often have difficulty being believed about the pain that they are experiencing.

Although physiotherapy cannot change endometriosis, just like we cannot reverse arthritis, there are many factors that a therapist can look at to help manage, reduce and improve symptoms. Think of the first thing you do when something is painful, say get a paper cut on your finger. You will pull the hurt hand/finger into your body, grasp it with the other side and squeeze. This instinct to protect the area that is painful is pretty universal throughout the body. What will this increase in tone and tension of the surrounding muscles of the pelvis do when repeatedly, month after month, the pain continues to return, do to the muscles? Determining the underlying factors, which muscles are more tense, what the surrounding tissue is doing, and helping come up with a home program can be beneficial in managing pain. Just as addressing muscle length and strength imbalances around an arthritic joint can make a difference in the clients’ pain, it doesn’t change the arthritis, it changes some of the other factors.

Managing these symptoms as soon as possible, will help to reduce the chronic pain cycle that often develops and persists for years.

Haylie has been practicing women’s health and focused in prenatal and post-partum care since graduating from the U of S MPT program in 2011. Officially adding to her practice pediatric pelvic floor therapy in 2017. She has been advocating for treatment for women, ensuring appropriate and effective care throughout pregnancy and post-partum, and helping all expecting and post-partum moms brought her to open her family-friendly clinic; where clients are encouraged to bring their infants and children to treatment. Adding pediatric pelvic floor. Warman Physiotherapy & Wellness has been nominated as a finalist for the 2018, 2017, & 2016 WMBEXA, is a WMBEXA award recipient of 2017, and a finalist in the ABEX 2017 & 2016, and Haylie was recognized as YWCA Women of Distinction for Health & Wellness in 2017.

Haylie has been practicing women’s health and focused in prenatal and post-partum care since graduating from the U of S MPT program in 2011. Officially adding to her practice pediatric pelvic floor therapy in 2017. She has been advocating for treatment for women, ensuring appropriate and effective care throughout pregnancy and post-partum, and helping all expecting and post-partum moms brought her to open her family-friendly clinic; where clients are encouraged to bring their infants and children to treatment. Adding pediatric pelvic floor. Warman Physiotherapy & Wellness has been nominated as a finalist for the 2018, 2017, & 2016 WMBEXA, is a WMBEXA award recipient of 2017, and a finalist in the ABEX 2017 & 2016, and Haylie was recognized as YWCA Women of Distinction for Health & Wellness in 2017. Globally with pain science, one of the most important things to understand are there are no pain signals to the brain. The brain receives information from the body, and depending on what all those signals are saying, will determine if something is painful or not. Have you ever stubbed your toe when you are having a great day? It hurts SO MUCH. But, if you stub your toe while you are in the middle of an argument with someone, it doesn’t hurt the same; that’s pain science!

Globally with pain science, one of the most important things to understand are there are no pain signals to the brain. The brain receives information from the body, and depending on what all those signals are saying, will determine if something is painful or not. Have you ever stubbed your toe when you are having a great day? It hurts SO MUCH. But, if you stub your toe while you are in the middle of an argument with someone, it doesn’t hurt the same; that’s pain science!

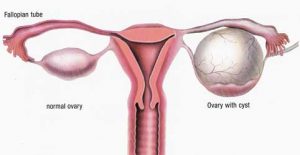

Thankfully, I was put on birth control, which seemed to make my periods manageable. My actual diagnosis of endometriosis was not until Oct of 2017. 6 Months prior to this I started developing excruciating stabbing pains in my right lower abdomen. A walk in doctor triaged me to the emergency room thinking my appendix had ruptured. Blood work showed no signs of infection, IV pain meds were given and an x-ray image did not show anything concerning. I was sent home with pain meds and told that I needed to poop. Exactly one month later (a month between my period) I ended up in excruciating pains where once again I ended up in the emergency room. This ER doctor again thought for sure it was my appendix but this time ordered an ultrasound. The ultrasound showed a 4cm hemorrhagic cyst on my right ovary. I was sent home with pain meds, and another ultrasound requisition. I was told to go see my family doctor in 6 weeks. I was told that a hemorrhagic cyst is nothing to worry about that it can happen with ovulation. My anatomy background and my knowledge of how a body works from also being a vet tech gave me a feeling that

Thankfully, I was put on birth control, which seemed to make my periods manageable. My actual diagnosis of endometriosis was not until Oct of 2017. 6 Months prior to this I started developing excruciating stabbing pains in my right lower abdomen. A walk in doctor triaged me to the emergency room thinking my appendix had ruptured. Blood work showed no signs of infection, IV pain meds were given and an x-ray image did not show anything concerning. I was sent home with pain meds and told that I needed to poop. Exactly one month later (a month between my period) I ended up in excruciating pains where once again I ended up in the emergency room. This ER doctor again thought for sure it was my appendix but this time ordered an ultrasound. The ultrasound showed a 4cm hemorrhagic cyst on my right ovary. I was sent home with pain meds, and another ultrasound requisition. I was told to go see my family doctor in 6 weeks. I was told that a hemorrhagic cyst is nothing to worry about that it can happen with ovulation. My anatomy background and my knowledge of how a body works from also being a vet tech gave me a feeling that  something more was wrong. The pain experienced during this time nearly made me pass out. Breathing hurt so I would hold my breath. I knew something wasn’t right. A 2nd ultrasound 30 hrs later showed that my cyst had grown by a couple of centimeters but that the radiologist wasn’t concerned as it’s just a hemorrhagic cyst and they can happen during ovulation. I wasn’t ovulating, I was at the end of my period. Something wasn’t right.

something more was wrong. The pain experienced during this time nearly made me pass out. Breathing hurt so I would hold my breath. I knew something wasn’t right. A 2nd ultrasound 30 hrs later showed that my cyst had grown by a couple of centimeters but that the radiologist wasn’t concerned as it’s just a hemorrhagic cyst and they can happen during ovulation. I wasn’t ovulating, I was at the end of my period. Something wasn’t right. I had honestly never heard of it before. I went home that night and did what most people do– I took to google. Symptoms of this disease was pelvic pain, which I did have prior to these episodes but chalked it up to the many bladder infections that I’ve suffered from. Extremely painful periods was another symptom, which again I had when I was not on birth control. Surely, this disease couldn’t have started at the age of 16. I kept reading, “many women with endometriosis suffer from infertility.” 2 years prior, I had a beautiful baby girl so I couldn’t much relate to that. Back pain can also be a sign of endometriosis. Sure, my back hurt, but I had also been diagnosed with scoliosis of my spine years earlier so my back pain was from that. “The feeling of your insides being pulled down”. My gynecologist asked me during one of my appointments how I was feeling. I told her “it’s like I’ve eaten Chinese food for all 3 meals a day. Like my guts are just so heavy they are all hanging below my belly button.”

I had honestly never heard of it before. I went home that night and did what most people do– I took to google. Symptoms of this disease was pelvic pain, which I did have prior to these episodes but chalked it up to the many bladder infections that I’ve suffered from. Extremely painful periods was another symptom, which again I had when I was not on birth control. Surely, this disease couldn’t have started at the age of 16. I kept reading, “many women with endometriosis suffer from infertility.” 2 years prior, I had a beautiful baby girl so I couldn’t much relate to that. Back pain can also be a sign of endometriosis. Sure, my back hurt, but I had also been diagnosed with scoliosis of my spine years earlier so my back pain was from that. “The feeling of your insides being pulled down”. My gynecologist asked me during one of my appointments how I was feeling. I told her “it’s like I’ve eaten Chinese food for all 3 meals a day. Like my guts are just so heavy they are all hanging below my belly button.”